Incidents - World War II

Adapted from an interview of H. H. "Tom" Odiorne by Bill Clagett - The Army Transport Service skippers in their 60s and 70s had a great impact on my skills as a boat handler. My other skilled trainer was the commodore of the huge Miami Yacht Club where I was stationed. In March of 1943 there was a "hush hush" VIP fishing trip for the day. The VIP turned out to be "Hap" Arnold who was recovering from a brief illness (maybe one of his several heart attacks). A couple of days later, while on patrol out in the Gulf Stream, we saw something that I remember vividly to this day. Off at the horizon in a becalmed sea, and under a brilliant sky, we stared at an orange colored sea. As we got closer we found that the ocean was full of floating oranges and fragments of wooden crates from an apparent sunken freighter, possibly a United Fruit Company ship. No survivors were found.

In the following months we made several deliveries of crash boats to the Naval Base at Guantanamo Bay, Cuba. We also made trips to New Orleans and way across the gulf to Brownsville, Texas. This was in addition to our routine offshore patrols of the southeastern and west coats of Florida. In late February of 1944 I met my future wife, a nurse in the Army Air Corps at the Nautilus (hospital) Hotel. Fortunately, our crash boats were now docked in Biscayne Bay, behind the Nautilus Hotel. She and the other nurses lived in isolated and well-guarded guest houses on an island adjoining the Air Corps Hospital. She was an officer and I was a mere PFC, so we spent much of our time dodging guards and MPs on dates. She and a girl friend used to row over to our docks in the dark to double date. After a brief courtship we married off base in Ft. Lauderdale, a few miles up the coast from Miami. Life was good, but about to change.

In mid-1944, with a shipload of GIs, I crossed the Pacific into another world. Never, ever, could I have imagined what the war would be like. I had been living in a military dream world, complete with sandy beaches, hotels, palm trees, girls, boats that looked like yachts, and finally, a lovely, very beautiful and caring wife. Once in the Pacific I saw a pure hell that for many years I have chosen to erase from my mind. Understand that I was nowhere even close to being a combat soldier or sailor. Most of what I experienced were the "leftovers" of battle. Our rescue efforts were concentrated on those poor souls, both military and civilian, who had been shot, maimed, or who did not make it to the beaches, or who were floating helplessly in the water praying to be seen and rescued. There were many that we could not, and did not, save. Out there nobody cared if I was a private or a general - and it would have been hard to tell the rank of any of us, because we lived practically every day in grubby shorts.

We made several attempts to respond to distress calls only to find floating debris and no sign of anyone to rescue. This changed one day in a monsoonal rain when we spent hours with other boats fishing bodies out of the rough seas from a downed transport plane that was loaded with Aussies returning south from a mission in the Dutch East Indies. We ran out of body bags and took the covers off our mattresses to stack them on deck for the return trip to a dock in northern New Guinea.

One of our more interesting missions was to carry a medical officer to various island villages where he tended to natives having the dreaded "yaws" disease. "Yaws" were large-to-huge blister-like growths found on people who live in the tropics. I remember that we took him to the Jolo Islands, Los Negros, Bohol, Cebu City, Puerto Princesa on Palawan, and several other islands.

My most gratifying experience happened when we received an urgent call to pick up a body at the end of a runway just as we were headed north to deliver a 63 footer to a base in the Celebes. An Aussie flying sergeant crashed fairly close to shore and was presumed dead. As we approached the wreckage of the downed plane we spotted the pilot floating face up in the water and we hauled him aboard, only to discover that he was very much alive but without his nose. That had been sheared off by the cockpit windshield. We were immediately instructed by radio to bring him to a field hospital. Not even two weeks later he came down to the docks looking for our crash boat to thank us for saving his life, He had a new nose, but one would never know it with all the bandages covering his whole face, but he was alive!

That is Tom's interesting crash boat service story. Tom, and others on this website, have made the service of crash boaters personal with their real life stories.

14th ERBS Historical and Intelligence Reports June 1944 through March 1946 - This collection of reports covers the actions of the squadron from the early days in New Guinea to the challenges they during the early days of the occupation on Japan. It covers missions and boats lost, along with individuals promoted, killed, or sent home for discharge at the end of the war. There is a large amount of information from their time in the Philppine Islands. Covering 44 searchable pages. The document is too large to include under "Missions", so I have placed it in "Manuals and Publications" section.

Be sure to checkout the OSS Operations for some really interesting accounts of their missions

10th ERBS From Adak to Kodiak January 6-10, 1945 - This is a personal log of the trip kept by an unidentified crewman aboard the P-216. The document is too long to include under "Missions", so I have placed it in "Manuals and Publications" section.

From the Lawrence Journal - World 6 May 1944 (Found on the genealogy site FamilySearch.org) Leaves from a war correspondent's notebook by Sid Feder, Anzio, May 1, 1944 (Delayed)

If you're around the Mediterranean battle zones some time and happen to spot a handy little gadget that looks like a surfboard with St. Vitus dance and behaves like a bucking bronco in a rodeo, don't be surprised. It's only a crash-boat.

The fellow who named this sea going instrument of torture ought to get a medal for the war's best job of calling them right. It knows all the old ways of whacking the waves and has invented a whole set of new ones to drive your backbone up around your neck.

This 63-foot craft is a Coney Island roller-coaster with salt water flavor. And if you want to prove it, inspect the collection of black and blue bumps decorating a traveler who has ridden one for the 90 miles between Naples and the Anzio beachhead.

In spite of all their tricks they're as useful a tool as Uncle Sam has roaming around the Mediterranean. They were built originally to handle rescue work for aviators coming down at sea. But since then they've covered an assortment of jobs all the way from capturing an island to running a bus service.

Lt Herbert Grant Prizer, who hails from Evanston, Ill., runs one that had its pint-sized bridge house blown away once by an artillery shell. This happened when it and a few more crash boats were participating in an attack on an island that enabled a force of 50 Americans to capture a garrison four times that large.

Another time a piece of shrapnel went clear thru the gun turret, which is about as big as a stall shower in the modern bathroom. As a souvenir, the shrapnel - about the size of a pie plate, is kept aboard by the crew: Warren (Brownie) Brown of Lemon Cove, Cal.; Vic Grossi and Lou James of Long Island; Lea Perjean of Lafayette, La.; Bill DeYoung of Patterson, N.J.; Jack Terry of Hammond, Ind.; the usual Brooklyn delegate, Whitey Nyquist, and a sea-going soldier, Cpl. Matt (Shorty) Majka, the army's assigned radioman from Star Junction, PA. Incidentally, James, after being away from home about a year, was sitting on the dock in Naples the other day and who should show up but his father. It seems pop is an engineer on a Liberty ship now.

If you're spending the night on a crash boat and there's an air raid don't worry about a thing. The roof of the cabin is of sturdy plywood - and the bunks are mattresses laid over large gas tanks. What could possibly go wrong?

A St. Lucian Cruise: Author; possibly George Dunning

We picked up our new boat at Dooley's (Ft. Lauderdale) and returned to Nuda's (Miami) for final outfitting. Our new orders specified that we were to deliver this 85 to an air-sea rescue crew stationed at St. Lucia and that we were to bring back the replaced boat to Nuda's yard on the Miami river. Specs on the replaced boat - UNKNOWN!

Sometime in August, 1945 we took off for St. Lucia, island hopping our way down. I remember San Juan particularly well. Coming into the harbor, we spotted a Navy destroyer. We were running low on provisions so we tied up alongside and asked if they could spare anything! The Navy eats very well; you would not believe the food that came aboard! When we arrived at Castries, the capital of St. Lucia, we hooked up with the crew down there. They were overwhelmed when they saw their new 85-footer and, of course, they knew nothing about her operation. We had arrived on a Friday; the next morning 26 of us took off for Bridgetown, the capital of Barbados, which is the eastern-most island of the Windwards, about 100 miles or so ESE of St. Lucia. This was a familiarization cruise for her new crew. We spent the night and returned the next day, a Sunday. Then they took us around the island of St. Lucia in their old boat - the one we were to bring back.

With a fair amount of trepidation and consternation we viewed "our next command"! It was an elderly (probably early 1930s) ex Coast Guard cutter. I must say it was spotless when we took her over, they must have put a fresh coat of paint over every square inch of her including everything in the engine room. She was powered by a pair of Kermath (cast iron!) V-12s which not only had considerable weight but also did not deliver much horsepower. She had respectable lines and was equipped with a steel mast with a crow’s nest at her flying bridge and a shorter mast with a cargo boom in the aft cockpit which they used to haul their dinghy aboard. In the engine room they had the same generator/ fire and bilge pump as we had on the 85-footer.

We departed St. Lucia on the 28th of August, heading almost due north to Antigua, where we would change course and headed due west, which meant we would have the easterly trade winds working for us. On the way to Antigua, about an hour out of Castries, the trades and the seas were right on our starboard beam, not conducive for a pleasant voyage in a round bottomed, somewhat top-heavy boat. We immediately decided that the heavy crows nest mast had to go, so within an hour or so, we had it lashed to the deck, which eased the rolling considerably. In the meantime, our 4-cylinder powered main generator decided to come to a halt. The engine gang tore it apart, did a rough valve job, checked and replaced some wiring and she started right up with all of us breathing a sigh of relief! The rolling stopped once we left Antigua, heading west, but we still weren’t making much speed, even with the following seas. Then the skipper had a marvelous idea. We had on board a large inflatable raft, complete with an enormous tarpaulin. Using the cargo boom we rigged up this tarp on the aft mast and I swear it added a couple knots to our speed. Westward we crept and just before docking at St. Thomas we noticed the oil pressure on the port engine behaving very erratically in spite of having plenty of oil in the engine. We cut down the RPMs and tried to nurse it along but to no avail; it ground to a stop as we docked.

So here we are, about halfway “home” and only one main engine, its reliability a big question mark. We were aware of a rather large air-sea rescue unit at Aguadilla, Puerto Rico, which was on the northwest corner of the island, large enough to have engine rebuilding facilities. We radioed ahead and it turns out they are in the process of rebuilding an identical Kermath to the one we burned out, a “port-sider”. Kermaths were installed counter-rotating, whereas Packards were all the same rotation, which could make docking a challenge. Understanding our predicament, they offered us their engine if we would help them finish rebuilding it. What a break! We limped int Aguadilla on the 7th of September and immediately set to work. Two days later the rebuild is completed and we removed our engine room deck hatch (a good-sized affair) to swap engines. No sooner we have the hatch off, the weather station at Borinquen Field issues a frantic warning of a hurricane headed our way and for all hands to make immediate preparations. With no hatch cover we crank up the starboard Kermath and limp out into the harbor where we set two anchors and lash down our trusty “square sail” tarp over the open hatchway. Fortunately, it was more than large enough. We managed to ride out the hurricane and it was a pretty good one. Back at the dock after things calmed down, we resume our engine swap and get on our way; we are way behind schedule.

We left Aguadilla on the 17th – ten days we spent there on this engine/hurricane “caper”! On to Santo Domingo, Dominican Republic; Jacmel, Haiti where we had stopped on the way down; then to Guantanamo Bay for refueling. Through the Windward Passage to Nuevitas, Cuba again. On the way to Miami, a long haul for our 83-footer in daylight – what happens? The oil pressure in our “newly rebuilt” plummets to zero; here we are again on one engine. We could not figure out what was wrong; we finally decided it had to be the oil pump which we could not possibly fix. The skipper figures that trying to make Miami in one shot is out of the question so he decides to head for Matanzas, Cuba, further up the coast and considerably less distance than Miami. On our way there we pick up radio warnings of another hurricane moving fast toward the west and we’re right in its path. Matanzas wasn’t too far away and we “spread-eagled” the boat in the upper reaches of the Matanzas River where it was quite narrow.

We got through that mess and Skipper says “Let’s shoot for Miami”. Now we’re running after dark – no running lights and a beam sea on the starboard; it was the remains of the hurricane. The 83 was rolling wildly and one wave threw Skipper from where he was sitting in the wheelhouse through the air to the opposite side, where he smashed his face against a porthole. He was a bloody mess but our surgical tech patched him up as best he could. Skipper was in quite some pain and shock but had enough sense to head back to Matanzas again.

The next day the sea had calmed considerably, so off we went to Miami. In the old cutter we crept north with the old girl rolling badly but nothing like the day before. Around 1:30AM we made Biscayne Bay; another 30 minutes found us at the entrance to the Miami River. After waking 4 or 5 bridge tenders, we limped our way into a berth. The skipper turned to give the engine cut-off signal and, before I could execute it, the engine quit and never started again. Our job was done – 11 days to get to St. Lucia in a new 85 and 36 days to bring back an old 83, not quite what our HQ had in mind!

The Crash of C-9453 Remembering a Veteran - An excerpt from Dad’s Memoirs Copyright © by Robert A Boyden

My Father, Donald Boyden, enlisted in the Navy during World War II. Due to his familiarity with small craft and his knowledge of Narraganset Bay and nearby waters he was assigned to the boat house at the Quonset Point Naval Air Station. What follows is the story of the demise of crash boat C-9453. I don’t recall his ever disclosing the cause of the incident but he does so in this story. It is transcribed from handwritten memoirs I discovered after his passing. I apologize for names that are misspelled or omitted and to readers who may not be familiar with some of the nautical references. To honor his memory, it is presented here as he wrote it.

Shortly after new year’s I was assigned to the 63’ crash boat C-9453 that a crew had brought up from Miami Shipbuilding Company in the last weeks of December. The skipper was Davey Carroll a boot lieutenant - green as grass. He had been a school teacher in Texas. Don’t think he ever saw a boat before but he was a 90-day wonder. He was a nice enough guy and said he did not know much. The first thing he did with us crew was call us together and ask the first class bosun’s mate and me to make up a list of gear that the boat needed. We gave him a list a mile long. Two very important items, as the lack of them later proved, were a spare anchor and line therefore. Much about this later.

The first thing he wanted was the sick bay aboard to be painted white enamel. What a job! The boat was built flexible and was comprised of many light closely spaced ribs and deck beams. The enamel was the best I ever saw but what a job to paint all those deck beams.

We did a little practicing with the boat and had a few skirmishes with some PT boats at Melville. They were a bit larger and had three engines similar to our two 1300 horsepower Packards. We kept up with them or edged them on occasion. What a bumpy ride in any sea. (We) had a civilian(?) assigned to the boat and after he was thrown against the overhead on his first trip he refused to set foot aboard again. Somehow, he arranged a transfer. There were some gasoline heaters aboard for several compartments. I remember one Saturday night in late January three of us had to spend on a mooring off Quonset for some reason rather than joyride inside the boat house (ashore) where heat was available. The temp was about 10 degrees outside Sunday morning and the heaters had given up the ghost during the night. We had slept with all our clothes on and also put on heavy fleece quilt outerwear. Brrrr!

Things progressed and we gradually were finishing many items to make us functional. However, on Saturday February 13, 1943 my watch had the week-end duty. We had gone to early chow at 1100 and returned to the boathouse. The other watch had taken off for the week-end ashore. About noon a big flurry of brass and gold braid descended on the boathouse and soon we were told to warm up the engines as there had been a plane crash in Buzzards Bay and probably we would have to go. Shortly, the skipper, Lt. Carroll, arrived at the boathouse and the boathouse day officer Lt. Petrie was with him. About 1200 we took off for Buzzards Bay. Aboard was Lt. Carroll, Cmdr. Petrie, Machinist Mate Bodtha, Bosun Mate First Class Barshof (recruited from the other boathouse crew as he had helped bring in the boat from Miami), Allie Osborn a signalman 2nd class, myself and several miscellaneous gold braids.

We went over to Newport and they opened the net gates for us to go out. When we got out around Brenton point and headed east for Buzzards Bay it was really choppy and uncomfortable. We had a fresh southeast wind and we were banging into some rough seas. I went below to get some binoculars for the skipper from his cabin and observed that the built-in desk that abutted a bulkhead pulled away from it about a quarter of an inch when we bounced into a few waves. She was flexible alright!

We arrived at Vineyard Lightship and went up Vineyard Sound to Quicks Hole where some fisherman had picked up the surviving pilot from the downed plane that had sunk off Quicks in Buzzards Bay. The decision was made to rush the pilot to New Bedford Hospital for a checkup. We arrived in New Bedford just before 1500. All gold braid and the pilot went to the hospital and were soon back. He was OK.

We started out for the return to Quonset in a strong snow storm. We made Hen & Chickens Light Vessel and set a course for Brenton Lightship. I had never been given the wheel for any length of time prior to this. When we got to the light vessel Lt Carroll said “take the wheel Boyden – course 270”. There was quite a sea running and the wind was west at 25 to 30 knots. We were rolling and twisting quite a lot. It took me a few minutes to get the hang of steering her and settling down to a more or less steady course. I kept thinking that they had not allowed anything on the course for the thrust of the wind and waves so I kept 10 to 15 degrees above the 270 (255 to 260) as much as I could. Whenever any of the gold braid got near I had to steer 270. We ran our time for Brenton’s and, no lightship. Visibility was probably a quarter mile at best. We slowed down and eased along for a bit and wallowed in the seas. Finally, I was directed to come about and circle. I picked as flat a spot as I could and made it with great rolling. Soon we saw a red buoy which had no identification on it.

About then one engine coughed off. Lt Petrie who was supposed to be a mechanic went aft to help. Buda was seasick in the engine room. Petrie soon got back and then the other engine quit. Ollie and I got out the light Northup anchor and line – the only one aboard - and put it over. There was not enough scope so we bent on another line and finally got the anchor to hold. The lines were only five eights diameter. From then – sometime around 1700 – we rode at anchor rolling and bouncing. All had been instructed to wear lifejackets. The snow finally started to let up so we could see shore. The Coast Guard Artillery picked up our blinker. They said a tug was on her the way from Newport to rescue us. We never saw a tug. About 1900 the anchor let go and we started our journey ashore at Cherry Point. On the way ashore we pulled all the bunk cushions into the cockpit for cushioning if we ended up against the rocky cliffs.

Bodke had been so seasick for a couple of hours that he lay in the cockpit as if dead. We had a tough time to get him up on his feet for abandoning ship. Ruskus too had been pretty sick. Ollie steered us in and eased us over a sand bar about half way in. The Coast Guard Artillery had a big spotlight on us all the way in. We ended up alongside a rocky ledge. All of us stepped on to a shelf like area and were helped up to high ground by the Artillery men and a rope. Not one of us even got our feet wet. The pilot had cheated death twice that day. The boat was being smashed very heavily against the cliff. We were taken to an Army mess hall in the carriage house of some big estate and enjoyed getting warm and eating. The temperature outside was about 10 degrees. After we had eaten and gotten warm Lt Carroll asked for volunteers to go back and see how the boat was making out. I went with 3 or 4 others in a Jeep. When got there the boat was still being smashed against the cliff, her decks were awash, the light on the top of her mast was still on and her flag was still flying from the gaff. We all slept like dogs that night in army barracks in the carriage shed or barn. Next morning it was clear, cold, west wind and pieces of the boat were match sticks all along the shore in the next cove to the east. The engines ended up in that cove. We all went back to Quonset in a Navy truck and were restricted for a couple of weeks until a court martial was held. We were all asked questions but no opinions. The next thing the chief examiner wanted to know was why the engines stopped. He never asked me thank goodness. We ran out of gas.

P-716 and P-717 arrived from Morotai (northeastern Indonesia) on the 21 Nov. 1944, after a gruelling 113 hour trip. During December 1944 the boats were active standing off Tacloban (Philippines) and Tanuan air strips on the alert each day. Several rescues were made during the period. The P-717 was given the task of taking a group of Intelligence Officers from FEAF around the island to Ormoc to investigate a new type of Japanese plane reported to have crashed in the area. During the mission the craft was subject to a strafing attack. Twin-fifties were subsequently installed on the bow of each boat as a result of the trip, as it was found almost impossible to bring the bridge guns to bear on a low flying aircraft approaching from directly over the bow.

During the month of January 1945 one of the 85 ft. boats was sent to Panaon Island, meanwhile the P-720 returned from a three day search mission on the 18th January with a score of 17 dead Japanese and three prisoners. The crew had been given information from a local informant on Carnsea Island which enabled them to surprise the enemy attempting to escape to Luzon. On the 25th January two boats including the P-716 departed for Mindoro and operational control of the 309th Bomb Wing. During February 1945 the boats were mostly on air strip alert duties or under repair, however four further craft which included two 85 ft. boats and the P-720 and P-717 were sent to Mindoro and then on to Subic Bay on Luzon.  The unit was still well dispersed, as six craft left Biak on the 20th February under navy tow – the boats included P-398 and P-718, both 63 ft. boats . On their arrival they made up half the HQ total boats, as only five 45 ft. boats remained at the base. The P-717 is recorded as having rescued 8 people on the 11th February in an operation off Pintayan. By the end of May 1945 the unit was based ashore, and also reported that five new 63ft boats arrived – all of which had to be fitted with radios on arrival.

The unit was still well dispersed, as six craft left Biak on the 20th February under navy tow – the boats included P-398 and P-718, both 63 ft. boats . On their arrival they made up half the HQ total boats, as only five 45 ft. boats remained at the base. The P-717 is recorded as having rescued 8 people on the 11th February in an operation off Pintayan. By the end of May 1945 the unit was based ashore, and also reported that five new 63ft boats arrived – all of which had to be fitted with radios on arrival.

Incidents – Between the Wars

Louis Risolio was at Langley AFB in VA as a cook’s helper when he got the chance to transfer to the Special Service Boathouse at Langley. They had row boats and sailing dinghies. I taught people how to sail, etc. One day I got a call and they wanted to know if I would like to help pick up a crash boat in Mobile, AL. I said, “When do I leave?” (I didn’t know what they were talking about or what a crash boat was.) So that’s how I got into the boat outfit.

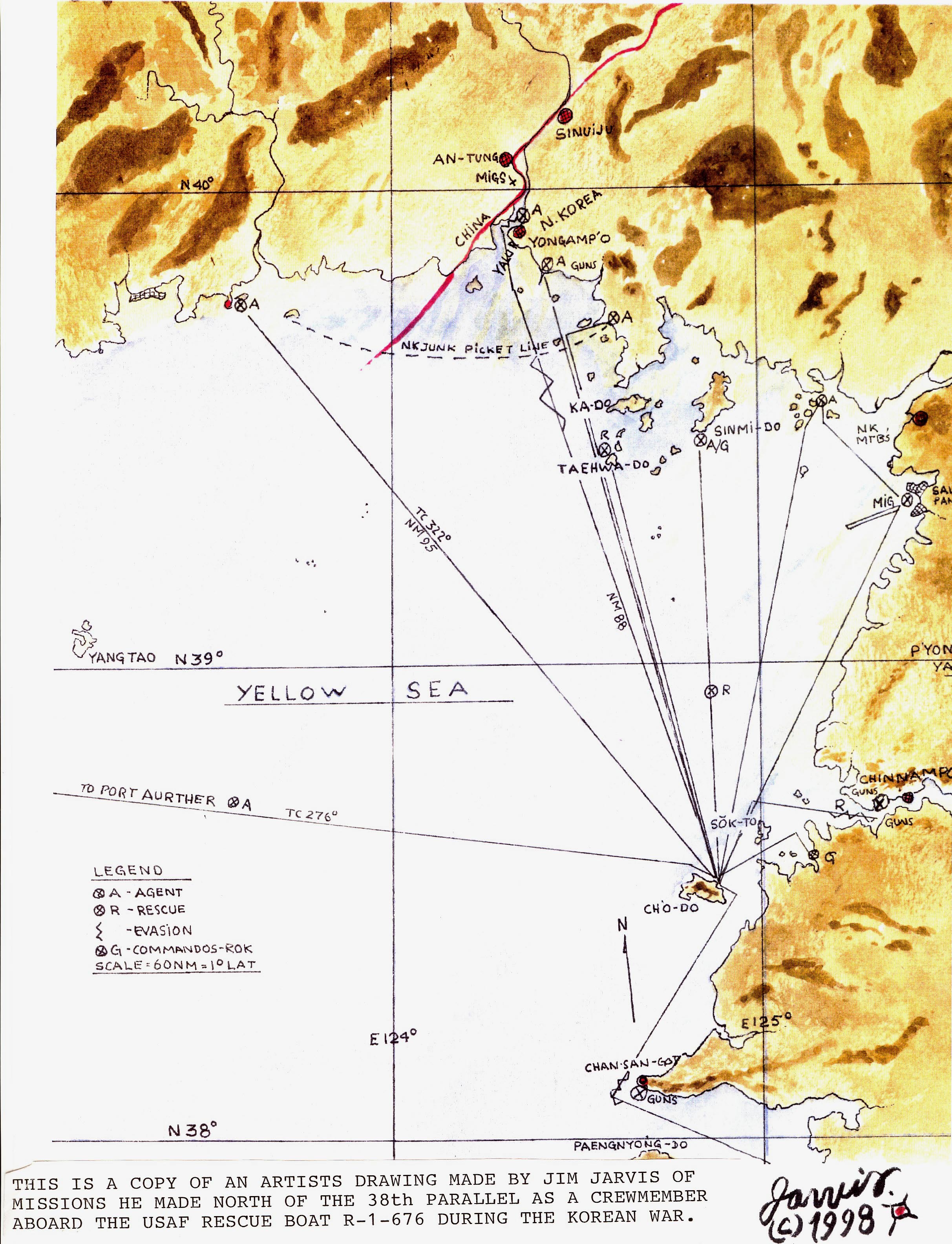

Later he was sent to the Philippines and when the Korean War broke out he was shipped to Fukuoka, Japan. He was assigned to the R-1-667 and later to R-1-676. He says of his military service: “It was a good life. I met a lot of good people and got my education the hard way. Would I do it over again? You're damn right I would…!”

Bolling Field & Pentagon Shuttle - Bolling Field has a long history, established in 1917, it is actually two separate military bases. Part of the real estate was called Anacostia NAS, with its own runways, and the rest was Bolling Air Field, with its set of runways. Just across the Potomac was Washington National (Reagan) Airport. There was legitimate reason to have a Crash Boat Flight based at Bolling, if only due to the dense air traffic. The unit began operations in 1941 and its primary mission was to provide water rescue coverage for all three fields. The Bolling / Pentagon Ferry service was established later.

Peter Kekenes shared information about his duty on a 42 ft. boat, RP-9-846. I was assigned to the Staff Boat in 1954 and 1955. The configuration was that of a 42 footer; after that all similarities ceased. There was varnish work inside and out, including a false mahogany transom with gold lettering. The deck fittings were all chromed, as well as the Danforh anchor. The aft cabin was reserved for generals. It was furnished with rich-looking blue cushions, and a coffee table whose top was made from a solid piece of black walnut. The boat's appearance made you feel like it was too nice to actually use ... that it should be kept in the boathouse and admired.

In October of 1954, Hurricane Hazel struck the Washington, DC area, with gusts up to 99 mph. Staff Sargent Bob Gordon, Sr. and I usually alternated morning and evening runs to the Pentagon. We assumed, due to the weather, that the evening run was canceled ... WRONG! Our office decided the run was still on. S/Sgt Gordon and I decided against taking another crewman to handle the lines. This way there were only two fools on the boat, instead of three.

I have never seen waves like those we encountered, not on an inland river. There is a junction where the Potomac River and the Anacostia join and just above it is the Washington Channel. Separating the Channel from the Potomac is Haines Point Park. Under normal circumstances, here are several feet of retaining wall between the river surface and the park walkway. When we reached Haines Point, it was completely under water and only the tops of the park trees were visible. Our greatest concern became that there might not be sufficient clearance to pass under the 14th Street Bridge. Our second concern was passing between the bridge abutments without smashing our hull.

The Pentagon Lagoon was next. The cleats on the retaining wall were under a foot-and-a-half of water. We held the boat off the wall and we dutifully waited for twenty minutes. We called the boathouse and were directed to return to base. I was reassured to find that, by the time an officer was promoted to general, he had picked-up enough good judgment to order his staff car so that he could travel in comfort and safety. The boat had following seas on the return leg. This called for large, constant corrections. An immediate worry was the state of our engines. S/Sgt. Bob Gordon recalls that starboard engine was overheating and when he reached Haines Point he shut it down and proceeded back to the boathouse on one engine. Upon returning to the dock, it was under water and only the pilings were above water. WO Rolf was the detachment commander and was knee deep in water, standing on the dock. Pete Sikes,who was the NCOIC of the night Alert Crew was also standing with him. Due to the high winds, Bob did restart the engine to use it backing into the boathouse.

Back in 1952, when George Zarvis arrived at Bolling, the boat complement consisted of one 42 footer (RP-9-1204) and two 24 foot J boats. The Ferry Service consisted of three 40' launches which carried a maximum of fifty passengers and two 42 footers (RP-9-853 & RP-9-953) for Air Staff ferry Service to the Pentagon. One of these was probably the former P-258 from Panama. Those two boats were referred to as RP boats; Probably to justify their existence (rescue) at the base. Yet in the 1950 redesignation of Army boats, P became R, but the 42' boats became U class boats.

The crash boats and the other available boats and crews experienced a few major crashes into the Potomac River. One of these was in 1948 or 49 when a P-38 and an Eastern Airliner had a midair crash while the airliner was on approach to National. All were lost except the fighter pilot, who survived after being rescued by the skipper, possibly MSgt. Flonlacker, of one of our boats. A short time later, a Capitol Airliner went into the river in heavy fog. Attempts to locate it were hard as we had zero visibility on the river but we got lucky when one of the boats almost ran into it. Zarvis recalled 19 were rescued thanks to Sgt Kissell, who was skipper of the boat.

There were several other incidents, crashes, etc. on the river, along with pleasure boaters and even excursion boats where drunks would jump into the river, some were OK, some drowned. Then there was the lady who jumped off the 14th Street Bridge and ended up on the boat, mad as hell at the skipper for not letting her die.

With the impending closure of flying operations at Bolling and the disbanding of Crash Boat Flights service wide, the crash boat operation was closed out, although the Pentagon Ferry continued. However, we were still expected to react to any waterborne emergency. We were out of the Crash Rescue business, unless there was crash boat business to be done..

During the final years of the shuttle service to the Pentagon, they were always trying, and usually succeeding, in cutting personnel and creating stiffer priorities for passengers using the ferry service. It got so bad that we had only one person operating each boat. Zarvis remembered once that when the staff boat made a run to the Pentagon with just a skipper. When it arrived and the Generals got on board, the lines were let go, everything went fine until the boat backed into the boathouse. One of the passengers came up and said there was a gurgling sound and the cabin was filling with water. All the passengers got off in a hurry and the boats was run under a crane where it sank in 4 feet of water. When she was hauled out, we found that the stern line was wound up into the prop and had torn the strut off. Whoever (passenger) let the line go didn't pull it into the boat and upon backing, it went into the prop. Needless to say, the one man operation was not popular after that.

The RP-846 was a 42 footer used as a Bolling AFB / Pentagon ferry. It was built in 1942 by Dodge Boat and Plane and was originally powered by two Hudson Invaders of 250 HP at 2100 RPM. Later she was repowered with two Chrysler M45-Sp3 of 275 HP at about 4200 RPM. She left Bolling in the late 1950s and went to Madagorda. In June of 1973 the boats made their last run and shortly after that the RP-853 was gutted, the pilot house cut off with a chainsaw, ports and anything of value removed, and the hull sold for $711.00 as scrap on a sealed bid. However, she reappeared a few years later as a pleasure craft on the Anacostia River. Zarvis went to work as manager of the marina at the base and acquired the 40 footers with the intent to use them as sightseeing boats but the cost associated with getting them to pass a Coast Guard inspection killed the plan and the boats were sold. George continued as manager of the AF Marina until 1992.

MSgt Rex Neptunus - MASCOT of Bolling Field's 21st Crash Rescue Boat Flight in the early 1950s. A black and white of uncertain lineage, Rex started his path to canine fame when he attached himself to the Crash Boat Flight... or vice versa. He soon adapted himself to the life of a rescue boat dog and became a skilled river dog.

When the crash alarm would sound, by day or night, Rex was always within earshot, sleeping in the alert room. He would leap aboard a boat and assume his duty station at the stern. He would remain silent until water came from the boat's exhaust, his bark was the signal to cast off. His personnel records show that he did go AWOL once for about four days and the crewmen were heartbroken. Finally he was located at the D.C.. Dog Pound. For his misdemeanor he was restricted to the compound for thirty days and reduced to the grade of SSgt. He was soon returned to MSgt.

Master Sergeant Rex Neptunus died 23 October, 1952. His death was attributed to the ingestion of rat poison which was put out by the bug people the previous day. He died surrounded by the crew and other friends. The boat crew buried Rex near the boat dock along the Potomac River and they chipped in to buy his grave marker as lasting evidence of the friendship and affection for the stranger of non-descript breed. Bolling Field, the boats, and the crews are gone but the marker is said to remain at the site to this day.

Korean War

R-1-667 - In late 1951 and continuing at least into early 1952, boats out of Cho-Do Island were harassed by “Bed Check Charlies” who flew over at night in their bi-planes and dropped hand grenades on them. Of greater concern were the MIGs from whom they would try to hide in darkness and fog banks. Mr Don Nichols, effectively field commander for special operations, personally recognized the achievements made by R-1-667, skippered by James Jarvis (now promoted from mate) as follows, “These men have been a great asset to this organization and their departure [to Japan] constitutes a considerable loss.” However, typical of special operations, this recognition came in a letter marked “RESTRICTED”. Three months later R-1-667, while operating in North Korean waters, came under fire and suffered “Holes in and through the planking on the port side, hot water heater jacket punctured, a hole in engine room blower, and various holes in galley compartment”.

The story continues,

We were chastised upon return to Japan after 3 months operating out of Cho-Do, that we should not have patched the bullet holes in our boat (R-1-667) with tin can lids because they rusted, and stained the paint! We should not have worn paratrooper coats and leather flying boots to keep warm; after all we were not in the Army nor were we aircrew. We should have sorted out the spent brass from the .30 caliber and .50 caliber guns into separate barrels before we turned in the brass for new bullets.

This was typical of the different mentality of officers commanding a desk rather than commanding men who were risking their lives. Winter temperatures in Korea frequently went below zero and the personnel in Japan were concerned about those airmen being “out of uniform” for battle, when no adequate uniform was available. Really?

Contrast the "uniform" of the crash boater to that of the submariner dressed for winter bridge duty in heavy wool underwear, a wool shirt, two pairs of special submarine trousers, three pairs of wool socks, aviator's fleece lined boots, plus rubber over boots. He then climbed into an additional pair of trousers lined with sponge rubber and put on more sweaters and a parka. Regular issue rain gear might be added if the weather was particularly foul. Finally two pairs of woolen mittens and sometimes rubber gloves over them. How he moved is beyond me, but he was certainly warmer than a crash boater on the bridge in a Korean winter.

Based on Jarvis’ experience on the R-1-667 and the U-52-1197, the Freight Passenger “mother ship” of the crash boat fleet off North Korea, the majority of the missions were not rescue. They were in support of intelligence operations – period! When a crash boat was discovered by the North Koreans or Chinese, it resulted in open combat at sea against armed North Korean junks, PT boats, and enemy aircraft.

Further, these operations ranged far beyond the so-called UN High Command boundaries. Crash boats and crews ranged from Port Arthur (China) up the Yalu River (China), all the way to the Russian waters off Vladivostok. Working through enemy picket boats to drop UN and South Korean agents, usually in the dark, without radar, without clear specific locations, directed by sometimes overzealous intelligence personnel, the crews prevailed to the man.

R-1-667 Bob Frankovich, skipper after Jim Jarvis, relates “… that two Australian pilots bailed out between Honshu and Korea. The Australian Wing Commander and his Adjutant wanted to see how we were conducting the search. We were out a few hours when the weather worsened. I told the Wing Commander that there was an island about ten miles away and that I was going to go in the lee of the island and ride out the storm. There was a radar site on the island and I called them to see if there was a dock I could tie up to overnight. They said there was but didn't tell me it was a forty foot dock and very difficult to get into. When I tied up, my stern was almost sticking out past the breakwater. A man from the radar site came out to meet us and I asked him what damned idiot told me I could tie up here. He was the Captain in charge and said he was the one that told me. He apologized and said he didn't’t know our boat was so big. I guess he thought I was an officer also, and I never told him any different. After a few minutes I left because my boat was getting beat up at the dock. The Aussies were able to spend the night at the site. We came back the next morning when the weather calmed down and picked them up. Later we took them back to Honshu. When the commander got off the boat he said, ”I thought flying fighter jets was dangerous, but they're easy compared to riding that little boat in that big ocean.”

Prior to the R-1-667 Bob had served in WWII, and in Korea as skipper on R-2-1196, a 63 that saw duty in zones K-3, K-8, K-9, and K-16 in South Korean waters. He had many other assignments in the Pacific, the U.S.., and France in the course of his service in the Navy, AAF, and Air Force. “My time in the boats was the most enjoyable. I made the best friends there. I had some good times and some sad times.” These sentiments have been repeated by several other crash boat veterans.

When he could, Bob traded 10 lb. bags of sugar for vegetables as crewmen were getting sick from a lack of vegetables in their diet. Technically that was illegal, but then technically they were not supposed to be there, and he could not complete his missions without a functioning crew.

Returning pilots “home” could be to a variety of places and generated a variety of “tips”. On returning a British pilot to a British ship, the commander of the ship asked if there was anything they needed. Bob responded that showers would be appreciated as it had been about 2 weeks since their last one. They were welcomed aboard and given clothes to wear and while they were enjoying long, hot showers, the ship’s laundry washed and pressed their uniforms. On another occasion, returning a Marine pilot to his base resulted in their receiving a large box of beef. All the beef in the box had been frozen together and the marine cook didn't want to bother to separate the steaks so he gave them the whole box. However, sometimes there was no “tip”. On returning a U.S.. Navy flyer to a ship, the commander wouldn't even let them top off their water tank.

Jim Jarvis, the skipper before Bob Frankovich, encouraged his crew to participate in all phases of running the boat. Francis Stroup said “We learned how to monitor the radios and to steer the boat or whatever, and I found for the first time in my life a sense of “belonging”. It was not until he was sent back to the states that he realized how much he missed the boat and the “buddies” that all of his shipmates had become.

Frank Trinceri spent the Korean War (6/1950 – 7/1953) in the Military Air Transport Service (MATS) but after the war, when he arrived in Bermuda, he was given the chance to go into a crash boat. He accepted with the condition that if he didn't like the duties he could go back to MATS. He served with the 6th CRBS until he was discharged in 1955. It appears that in spite of the hardships associated with the duties, the men who got into crash boats liked the service. There is a gallery for Bermuda photos in the Photos & Missions portion of this website.

R-1-667 (again) Bruce Miley had earlier served on a 63 at K-2 and K-14 (a small air field south of Inchon. He served on 667 for the last 90 days of the war. “Cho-Do recalls some scary moments, like when we started up the Yalu River and hit a sunken Japanese battleship, tearing our rudder about in half. One of the guys dove into the cold water and tied the rudder so we could go straight ahead.

Once we had to go to the aid of a British ship with many wounded, to have our medic assist them. In return they gave us some mutton, which we ate for our last 30 days on station. That incident happened because the ship’s commander told his men to “load and fire” but not in what quantity. By the time they fired their last rockets, the “gooks” zeroed in on them and blasted the hell out of the deck.

Francis Stroup remembers that on another assignment one night and anchored at some little island awaiting orders along with several ROK Navy boats nearby, a B-26 happened to be heading back from his sortie and spotted a light where the pilot knew there should be no lights. "He also just happened to have a 500 pounder left. He figured he would be better off to get rid of it, so he dropped it right in our midst! It was 'all hands on deck' in about a split second. Luckily for us, we were not damaged."

Extracted from The US Air Force Air Rescue Service by Wayne Mutza - After reporting problems with two engines on October 31, 1952 a B-29 bomber returning from Korea to Kedena AFB, Okinawa was met by a search and rescue SB-29. When a third engine quit, the bomber had no choice but to ditch in the sea. SB-29 crew lost sight of the bomber but dropped its lifeboat in an area lit by a flare. The flare burned out, causing the wreck and the lifeboat to disappear in the blackness. An H-19 helicopter that had been dispatched was led to a light spotted by a SC-47crew that had also responded to the scene. The H-19 crew lowered its sling to pick up a survivor but backed off as a crash boat (length undocumented), which could make a safer pick up was approaching. The H-19 continued to light the area while the crash boat rescued two additional survivors.

Boat Beached at Ashiya – A P-51 Mustang crashed on the beach not far from its base and as luck would have it there were two 63 footers in the area. Jim Connors was tied up to the bridge up the Ashiya River and my boat (Tom Gould writes) was on the way to relieve him, so Jim got there before I did. It was right at dusk and the tower at the base thought he went into the drink but he crashed on the beach, right at the water’s edge. Jim could see him through his glasses as the pilot was walking around in a daze and they could see that he needed help by the blood on his face and head, so Jim put a raft over the side with the medic in it but it capsized when it hit the surf. So Jim’s next move was to beach the boat to give aid to the pilot, which he did as it took the base quite a while to get there due to not having vehicles that could make it through the sand or over the dunes. It was believed that Jim’s action saved the pilot’s life as he was in bad shape.

Then the fun started, getting the 63 footer off the beach! Jim drove it on the beach bow first at full bore with a heavy surf, which really helped to put it high and dry. I should mention that I got there right after the beaching and swung on the hook overnight. Well, the first thing we did when it got light enough to see was to row ashore with a couple of my crew to see what we could do. The first thing we had to do was to pull the props, shafts, struts and rudders. Then we got bulldozers from the base to dig around the hull, sort of built a dry dock. By doing that the hull sank lower in the sand but we had to be real careful so as not to tip it on its side. So, after all was done, I went back aboard my boat, then got a line to the stern of Jim’s boat, then had a dozer break the dam at the end of Jim’s boat, then with a dozer pushing at the bow and us pulling at the stern, we got it afloat. We took Jim’s boat on the hip and hauled it back to Fukouka. After we tied up eight or nine men collapsed from exhaustion. You had to give those guys credit, they wouldn't’t give up ‘'til those two boats were tied up and secure. Jim and I went to the club and opened the bar, had a few drinks, and fell asleep right there on the bar. No one ever said a word about it, I guess they knew better, we were beat.

We didn't’t have a boat basin at the time (at Ashiya?) so we tied up in the river with stern lines to the bridge and an anchor off the bow. Conditions weren't’t the best as the crew had to stay aboard at all times.

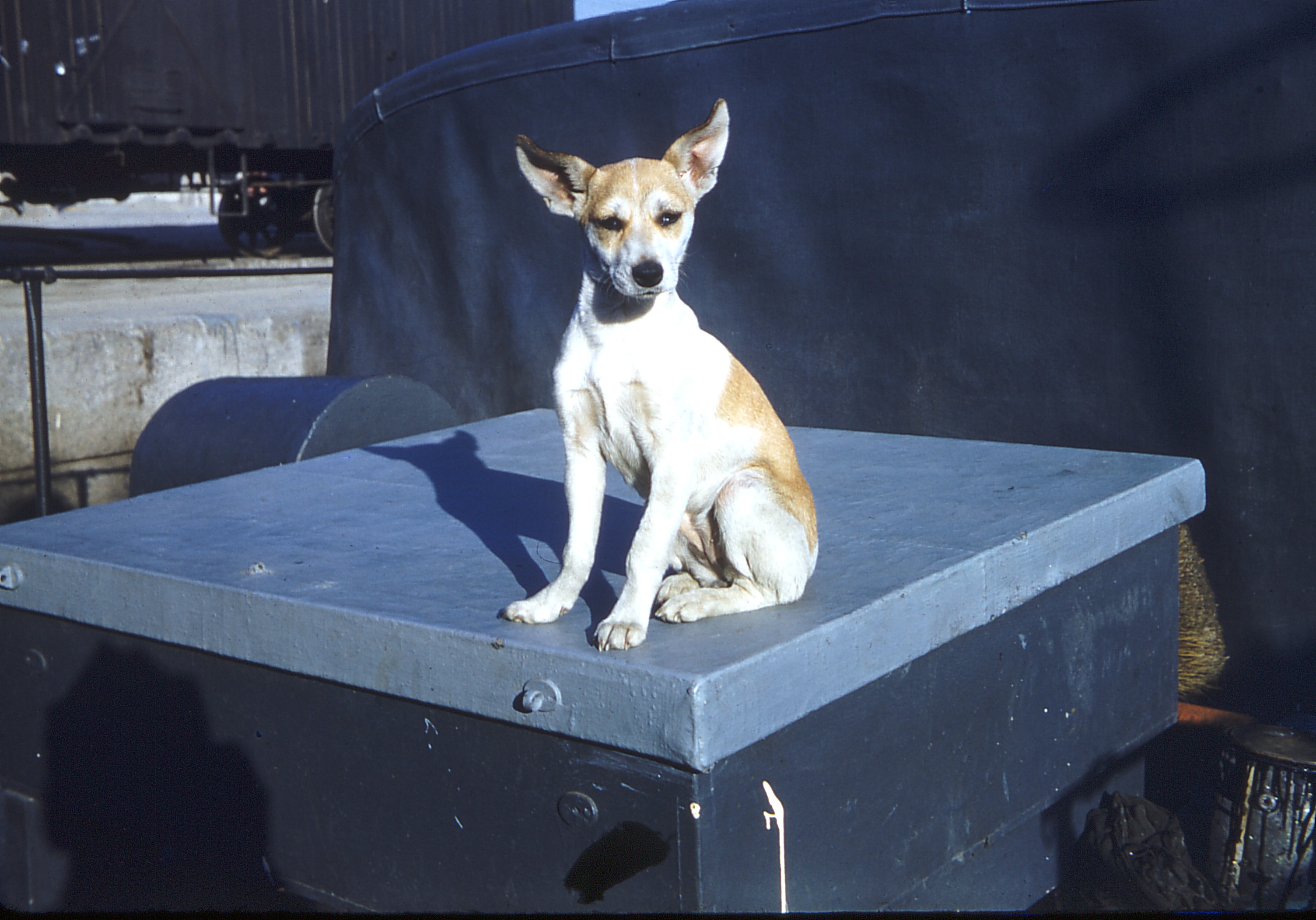

Milton Seagraves- We had a small dog on R-1-664 and her name was "Eightball." One of the other crew members (Keithly) brought the dog on the boat. She liked to drink beer and some of the guys gave her too much beer and she got drunk.

She fell down some ladder steps about four feet and broke her left front leg. We put it in a splint until it healed. Live mascots were fairly common on the boats. The P-399 in the southwest Pacific had a dog named Salty and later a monkey for a short time. In Hawaii, one of the boats at Hickham had a dog named Skipper in 1954. There were many other mascots that I have not recorded.

Standing guard at night on the boat was very difficult. The nights In North Korea were total darkness. You could not see your hand in front of your face. The noise of the wind blowing across your ears and the waves lapping on the side of the boat made it hard to hear much of anything. The dog had very keen hearing and she always stood guard with me and others at night. As I recall, guard duty lasted for two hours.

One night about midnight, when Eightball and I were on guard duty, she started making a low whining noise and I knew something was going on. If I listened very closely, I could hear the distant sound of an engine running at a very low RPM or just idling. Feeling my way along the boat in the dark, I went to the stern of the boat and called to the South Korean house boy (Kim) to come and challenge the intruders. The house boys were also our interpreters. The boat crew is never in a deep sleep. Anything out of the ordinary would always bring several of the crewmen checking to see what was going on. In just a minutes, our boat was a beehive of activity. The skipper turned on the spotlight and lit up the North Korean junk. The house boy went to the bow of the boat and called to them. (I don't know what he said but it was probably "who goes there") No one answered but I could hear the anchor chain clink as the anchor was being lowered. The house boy called again and still no answer. By now, our engines had been started and the anchor line removed. Members of the crew were standing topside with guns. One of the men standing near the bow, shot a machine gun over their heads and through the reed sails. Immediately, a man appeared on the deck and began to shout very loud in Korean with his hands up. Suddenly, the lid to the engine room opened very quickly and out of the heavy diesel smoke came the engineer with his hands up speaking very loudly in Korean. We moved a little closer to the boat but still remained 100 feet away. The skipper contacted the Cho-Do Island Command on the radio and told them about the intruding North Korean junk. They sent a small boat with South Korean soldiers. The two men were taken away as prisoners. I don't know what ever happened to the men or the boat.

R-1-664 – Bud Tretter recalled that “during the winter the North Yellow Sea iced up to the extent that at times we were iced in and you could walk around the boat on the ice. Occasionally we would use a bazooka to blow holes ahead of us to break up the ice so that we could launch a mission. The cold was so intense, 10 to 30 degrees below zero that we stood only 30 minute watches. By the same token it got just as hot and humid during the summer. Due to the ice during winter, most of our special ops were carried out during the summers or when the ice was not so bad in winter.

Most of our missions (on the 664) were to insert teams of spooks into North Korea, Manchuria and China itself. Places we were not supposed to be. Special Operations 5th Air Force was run by Mr. Don Nichols who kinda reminded me of Marlon Brando in Apocalypse Now. Unfortunately Nichols loved our 85 footers and dreamed up all kinds of things for us to do. It was fairly common for all the boats to insert spies and counterfeit money, ration and identification cards, anything to undercut their economy. We have tied up in the Yalu River for 3 days, waiting for a team of spooks to return, with MIG’s passing over head from their base at Antung Manchuria, we had running gun battles with big diesel powered junks; we strafed little fishing villages at night, operating together with South Korean Elco PT boats. (They originally had 8 boats, but had lost 4 to gun fire).

One of the good things Nichols did for us was to classify our rank. We wore no rank insignia’s. We carried no I.D.. other than our dog tags. There were a couple of good reasons for this. We carried no officers aboard the boats. The boats were manned solely by enlisted personnel. The officers (including skippers) of U.S.., British, and Dutch ships operating in the area did not know anything about us and it was thus easier to get fresh water, food, ammunition, and to take and occasional bath – always in officers’ quarters. The other reason was that many times we were in places that we were not supposed to be and in case of capture, all that they would get was off our dog tags- name and serial number.

When the shooting stopped in June of 1953, I stepped off the 664 and never saw her again. In 1957, the Air Force dis-banded all rescue boats worldwide.

R-1-664 - Robin Lloyd was Master of the vessel and a certified “Character”. His typical uniform was an Air Force blue overseas cap, bell bottom dungarees, blue shirt with white nylon laces, and his English accent. He was born British but became an American citizen during the war. Robin was at one time a Mate on a British ship. He was a speed reader, reading paper back books in 20 minutes. He was an expert at sending messages in Morse Code using the semaphore light and the semaphore flags.

He came to the U.S.. and his parents owned the "Turn About Circus" in Los Angeles, CA This was a puppet show and at half time everyone got out of their chair and the back row rotated to the front. Those in the front row during the first half were now on the back row for the second half. After he left the USAF be went to Mexico and became a Matador.

Among the many stories about him is the following, as remembered by Bud Tretter:

“I was a member of the R-1-664 while Robin was the skipper. There was a time when the 664 was returning to Cho-Do from a mission up the Yalu River. Upon arrival at Cho-Do, Lloyd had radioed a message to the personnel on the shore station that he was in route with an estimated time of arrival. Upon approaching the harbor at Cho-Do, the 664 was told not to approach and to moor to a floating buoy in the outer harbor. Lloyd then sent a message identifying his boat and that he was proceeding. The shore again warned him away from the anchorage. Lloyd them relayed by Altis Lamp, in Morse code, the following message, ’If we are not granted permission to anchor, we shall open fire with our main batteries!’ After a pause, the 664 was allowed to proceed into the harbor.”

I guess that he had enough of a reputation as a “loose cannon” that it was not a safe bet to call his bluff. But then you had to be a little different to live the crash boat life.

On one occasion on our way to Inchon, from Fukuoka, Milt Seagraves remembers, we had a drive shaft bearing go bad. We stopped near K-10 in southern Korea and an aircraft delivered us a new universal joint in a canister via air drop. The parachute was a bright orange. After installation of the new universal joint we proceeded to Inchon. A day or two after we arrived at Inchon it was necessary for some of us to go to Seoul and visit Don Nichols. We took the jeep and proceeded to Seoul. On the way, it became known that we did not have a pass to get onto the base where Don had his office. Lloyd suggested that we tear the orange parachute into large squares and use it as a kerchief to put around our necks which we did. As we approached the gate, we all saluted the guard and he just waved us on to the base without checking anything.

Post Korea Recollections

Joe Boyle was just a teenager in the mid to late 1950s and his first real summer job was working in a small boatyard in Tampa that was modifying two 72 ft. crash boats. The boats were in two different yards, but both yards were owned by the same partners. He didn't have much information on the boats except that they were originally built for BuShips (U.S. Navy) and that they were stationed at nearby MacDill AFB. From the data plate on the one boat he worked on, he learned that it was built at the Deer Island Yacht Basin, in Stonington, ME. However, he does not recall the year they were built.

72s had a pretty typical crash boat layout; below from the bridge or pilot house was the radio shack, then a galley with and electric stove and eating area. From there you went through a bulkhead to the crew's quarters, which consisted of four pipe berths and an unenclosed "head". Officers' quarters were aft of the galley on either side of the boat. Behind that came the engine room with two Hall-Scott Defenders and two generators powered by two small four cylinder engines. Both boats were painted with little bright trim, but what trim there was, was mahogany.

The two boats were in the yards to be modified for missle or nose cone recovery. Since this happened about 60 years ago and he was a typical teenager, details are a bit fuzzy. The boats came in with drop type transoms but were being re-coverted to standard transoms and a derrick was being added. In addition, the hatch in the forward deck, which was originally of alluminum and easly handled by one person, was replaced with a bronze hatch with a collar that elevated it about a foot off of the deck. The casting was about an inch thick and was difficult for one person to open, not good for an escape hatch. To see photos of 72' crash boats, go to Photos & Missions, then select World Warr II.

Adapted from an article by William Smith - William Smith, A1C, was in the Navy from August, 1952 to June, 1954, then in the USAF from April, 1955 to February 1959. He was an engineer on R-37A-1276, a repurposed crash boat. He was also a rescue diver during Operation Hardtack at Eniwetok in the Marshall Islands in 1957. His duties included constant exposure to nuclear radiation on the island and in the sea while testing the water. He was one of the two top divers. Individual hazmat suits were nonexistent in those years. In fact, an internet search will yield a number of photos of men working Operation Hardtack with nothing more than swimsuits.

Operation Hardtack was a series of 35 nuclear tests conducted by the United States from April 28 to August 18, 1958 in the Marshall Islands at Eniwetok Atoll and the surrounding area. At the time of tests, the series included more nuclear detonations than all prior nuclear explosions in the Pacific Ocean combined. These tests were part of a bigger series which ran from 1957 to late 1958. The series involved over 19,000 people from the Department of Defense, the Atomic Energy Commission, and other federal agencies.

There were three main research goals. The first was the development of new types of nuclear weapons. The second goal was to examine how underwater explosions affected materiel, especially Navy ships, and was conducted in both open ocean and in a lagoon. The third objective was to analyze high-altitude nuclear tests in order to refine the detection of such tests when conducted by the Soviets, the effects of such tests on the ozone layer, and to investigate defensive practices for combatting ballistic missiles.

William was one of a crew of six men aboard the R-37A-1276 and the only survivor as all the others have died of cancer. Years later he also developed recalcitrant skin lesions diagnosed as basal cell carcinoma, squamous cell carcinoma, and melanoma. William underwent surgery and radiation treatment for the melanoma on his scalp. His scalp was removed six times between 2008 and 2013 to remove melanoma. He was treated with chemo and radiation. The radiation affected his skull which developed osteomyelitis, which required treatment with IV antibiotics for two months in 2013. The radiation was so intense that it caused burns to the side of his face as well as his body down to his waist.

William also recounts another hidden hazard on Eniwetok, the number of suicides there. He was aware of at least 13 deaths while in the area. These were mostly military personnel while on active duty in peace time. He also recounts that he received full compensation for his injuries in 2013 and says it took the V.A. a long time to come through with coverage of the injuries they knew he received from those tests.